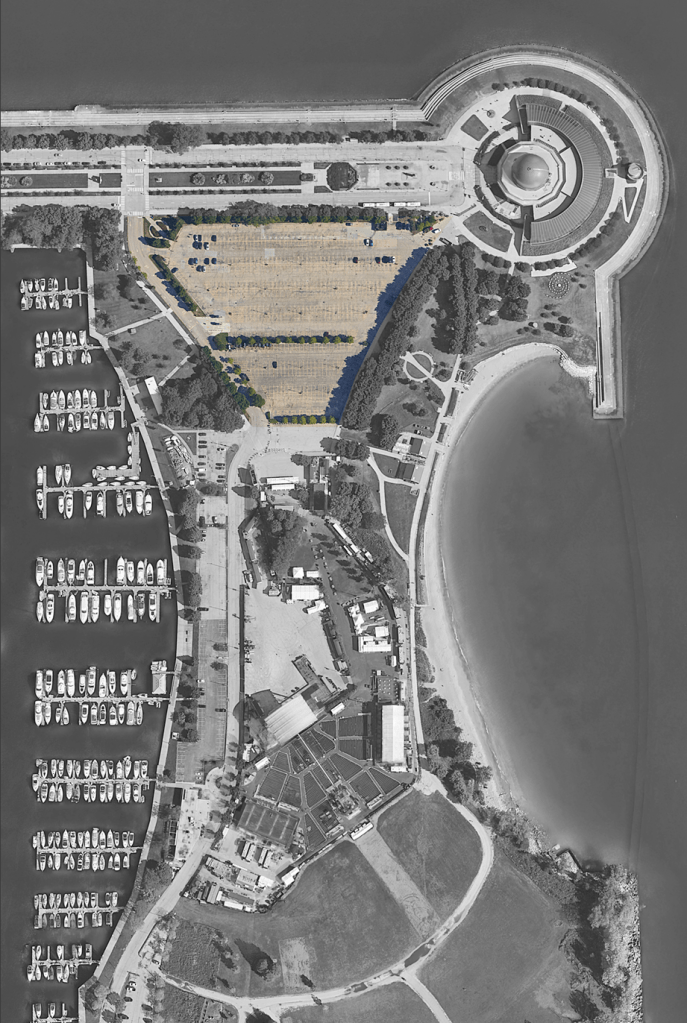

This academic project involved the conceptual design of both a museum and school of music on Northerly Island in Chicago.

The site condition alone was more than enough to work with; any design would have to reconcile and acknowledge the site – what is currently a vast parking lot – as positioned critically at what is arguably a pronounced intersection of the city and the lake.

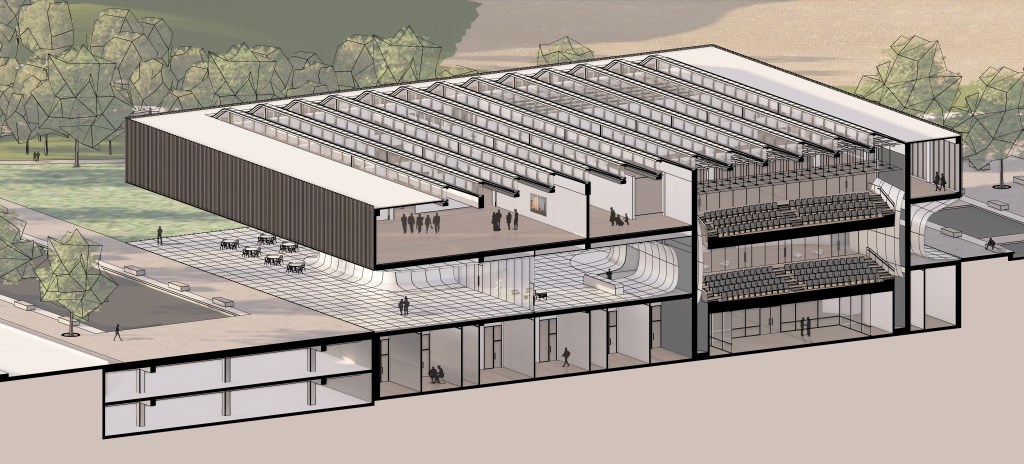

The form of the project, consequently, capitalized upon this intersection and sought to further the condition by effectively layering the programmatic requirements – a museum of sound, a school of music, and a newly instituted intersectional space, which would act as social lobby and circulatory space between the two main programmatic halves.

As the concept developed, however, it became necessary to dramatically expand the contrast between these (now two) very distinct things: the program as required & the architecturally supportive program.

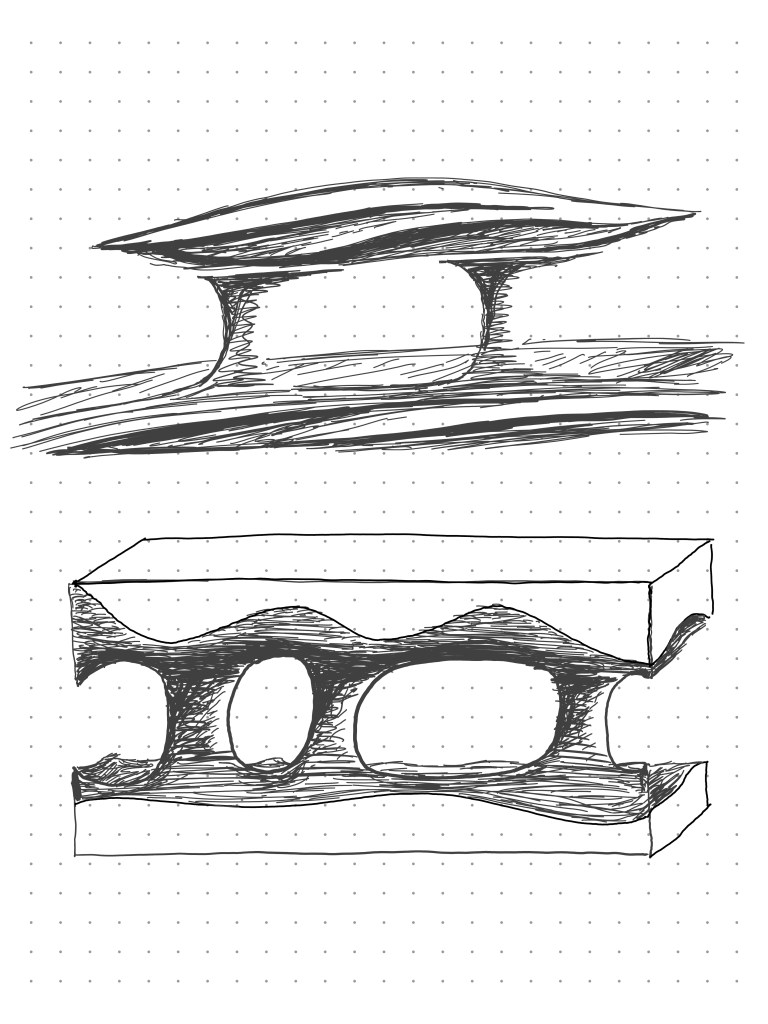

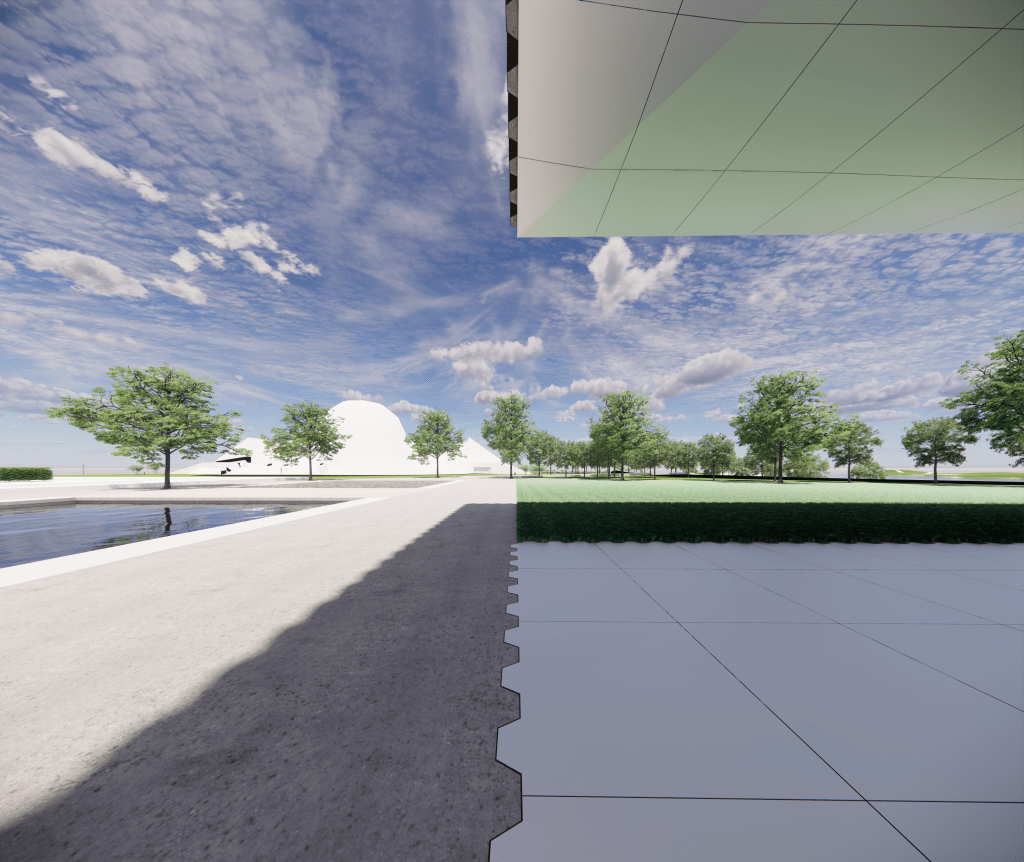

Thus, an overarching dichotomy was established; the intersectional level would act as a completely unique and fluid layer suspended within what would otherwise be a rigid, structural form.

This aesthetic relationship would not only mirror the dynamic nature of the lake against the city’s edge but would also – crucially – provide justification for the newly implemented lobby level not as an additive, active decision, but as an unavoidable conseqence and result of architectural erosion.

But what materials would come to define this dichotomy? If the intent was to seemingly carve from a singular volume, how could two languages be made distinct but never separate?

It seemed for a while that the facade (and thus the DNA of the primary volume) could – in theory – be made of any material, as long as it was not the same as the material below. Would it be solid or transparent? Reflective or matte? Perhaps it was made of bricks, artfully sculpted to reflect the waving nature of the lake?

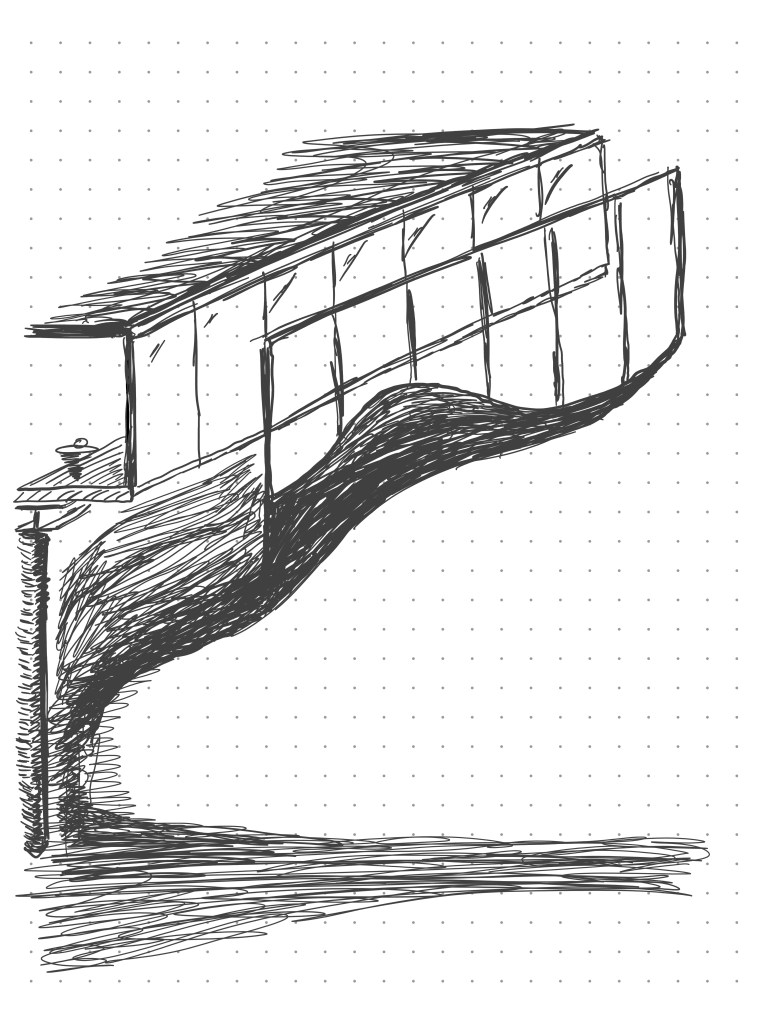

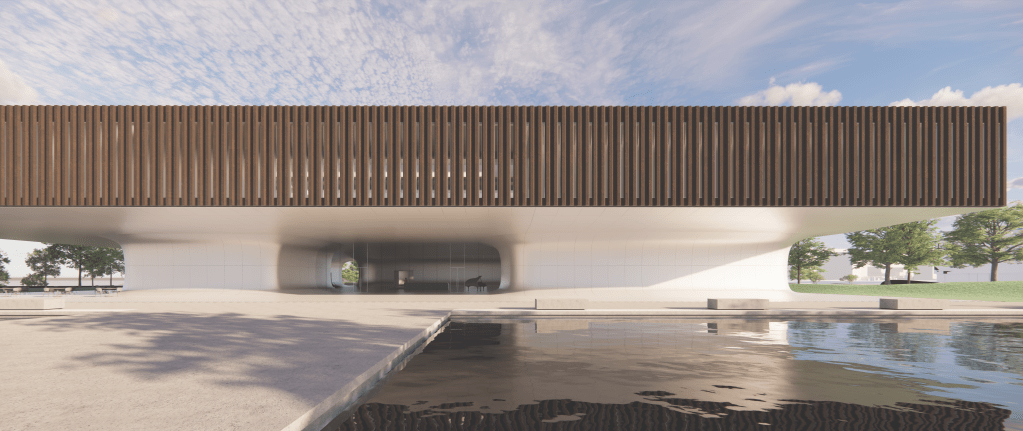

Due to the sheer scale of program there was a natural lengthening to the architectural form and, after countless variations and attempts to solve the material puzzle, the conclusion was that the material need, above all, possess strong verticality to not only bolster the design idea of the diametric but limit the condition of direct daylight into the sensitive museum space within the upper level.

Thus, a corrugated corten-steel facade was selected as most appropriate given these considerations and those justified technically by the structure and geographic location. While the pre-weathered steel provides ample protection against future weathering, the corrugations recess the glazing, limiting glare by preventing direct sunlight from entering.

It was only after the semester ended that I noticed the resemblance between the chosen facade and the Chicago shoreline.

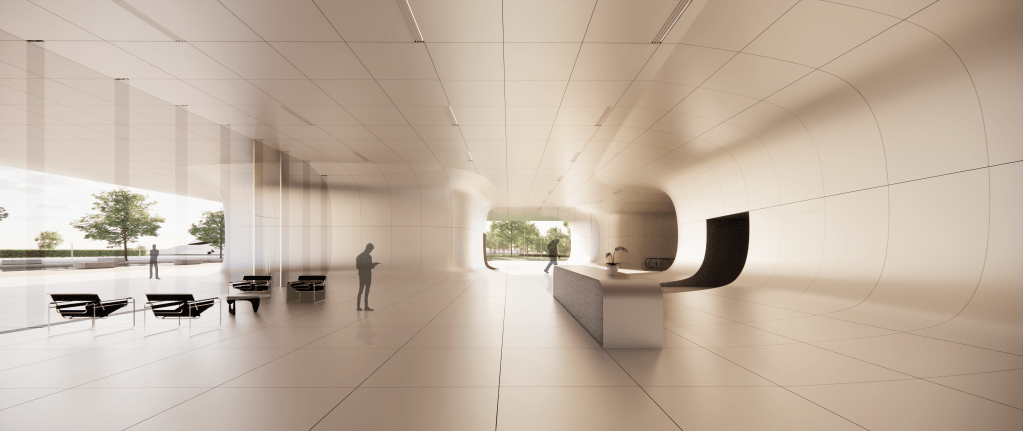

So what, then, did the “weathered” layer look like? If the upper facade represented rigidity, form, and order (with no apparent shortage of sharp edges), then the interior must simply be the opposite.

Smooth, planar, and edgeless, a precast panel system was selected to “enclose” the ground level. The image below shows, among other things, how doorways would simply be panels removed from the grid and specialized furnishings – such as the front desk – would be stretched castings filled with concrete.

These doorways would lead into two double-height recital halls and one triple-height orchestra hall, programmatic components which indeed acted as intersectional spaces between the museum (on the level above) and the school (in the level below). Thus these “cores” would come to define the only boundaries of this middle level, connected gently with an enclosure of glass.